"What I strive to understand is how I can learn from him"

On Telepathy, Letting Go, Digging In, and the Struggle to Find Common Ground

On a cool morning in September of 1987, biologists Warren Parker, Chris Lucash, John Taylor and Mike Phillips left the houseboat on which they were staying in the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge and rode a small Boston Whaler through swampy inlets toward a pen where a red wolf pair was being held. “Calm weather made for a smooth ride,” Phillips would write later in his field journal, “but added to our anxiety because we knew that wolves 140M and 231F could hear us coming.”

140M and 231F: so named because they were the 140th male and 231st female descended from the initial group of founding wolves that had been plucked from the wild, bred and cared for by humans at the Point Defiance Zoo on the far side of the country, in Washington state. The men switched off the boat’s engine and “floated the last fifty yards” in attempt to be as quiet as possible. Then two held the boat while the others lifted a hundred-pound deer carcass out onto the shore, to be left as initial sustenance and perhaps to entice the wolves out of their enclosure once the doors had been opened. These were to be the first red wolves back on the landscape where their kind had roamed for thousands of years, before being eradicated from it; the first of what conservationists hoped would be many more to come. Two men carried the carcass off through the marsh, toward the pen; they came back twelve minutes later, “breathless, anxious…unusually quiet. Taylor said nothing,” Phillips wrote, in a now oft-quoted account, “but Parker uttered, ‘We did it. We let them go.’”

Even here, in this observation from the earliest moments of red wolf reintroduction, the struggle, uncertainty, and paradoxical qualities of rewilding are evident: the need for intense human care, labor and concern, all in service of freeing a creature from these same constraints. The mere act of letting go is, in many ways, a conscious and deliberate one—we did it, Parker says—invoking both decisiveness and cooperation and, inevitably, ownership of mistakes. As in life, there is push and pull here, nuance and contradiction, even in the simple-seeming act of release.

Subadult red wolf in Alligator River refuge, photo by Bob Bowen

I first learned about red wolves just a few years ago, in 2018. I found unexpected solace visiting a family of them at a science museum near my house in Durham, four hours by car and worlds apart, in many ways, from eastern North Carolina. A litter of pups had been born at the museum that spring, and at that point in my life—the midpoint of Trump’s first presidency—seeing a daily onslaught of headlines warning of melting ice caps, attacks on journalists, and families being torn apart at the border, such hopeful moments seemed in short supply.

I was fascinated to learn both how endangered they were and that their last stronghold on Earth was right here, in my home state. But just weeks after this discovery, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, the federal agency responsible for conservation of endangered species, proposed shrinking red wolves’ last protected habitat by ninety percent and letting them be hunted. This move would effectively condemn the wolves to extinction, despite the agency’s mandate to do the opposite. I was mystified. (The proposal was later withdrawn).

My intrigue soon turned to bewilderment and anger. I knew that wolves were controversial, in general—I’d heard the fairy tales, of course, and seen countless movies in which they are depicted as bloodthirsty, demonic beings. I was also vaguely familiar with anti-wolf sentiments out West, where ranchers have long sparred with them amid vast tracts of federal land. Yet still I wondered why a recovery program that had served as a model for other successful predator reintroductions worldwide would be effectively dismantled from within, after just a few years of struggle.

I began to dig deeper. And over time, as I entered the orbit of the zealous advocates both for and against red wolves, I came to see that the fierce fight over their existence in this rural sliver of America was in many ways not even about wolves—as I may have mentioned in this SubStack already, and as folks on both side of the divide have told me, more than once. I’ve more recently begun to think that inaction or indifference may be the wolves’ worst enemy, along with differing human interpretations of freedom—whether individual property rights trump a wild creature’s right to exist—and the seeming impossibility of those with opposing worldviews to meet somewhere in the middle.

In red wolf country, hunting is a way of life, both for subsistence and as a major source of revenue for the community. Sea-level rise is also adding thousands of acres of ghost forests—swathes of skeletal, salt-choked trees, rising up from the swamps—to the landscape each year. Some residents blame the rising water on federal mismanagement of wetlands. Some are necessarily more concerned with their own survival than that of an endangered canid. Advocates for the wolves have kept telling me that compromise is essential if they are to have any hope of enduring in the wild.

Working on a book about this effort, I’ve been trying hard to approach this conflict with an open mind, to listen to all sides, to try to understand worldviews different from my own. I set out trying to understand—why there was still much animosity in the recovery region; if there was in fact hope for a species if even would-be protectors fell short (or were stretched so thin as to be rendered unable to protect them)? I’m still asking hard questions—which I guess is a way of saying I haven’t found the answers: is there any chance of such animals thriving on their own without protection? If not, what does that say about where we are headed on planet Earth? I’ve described this book as a story of struggle and survival that illuminates the often painful, at times transcendent experience of seeking hope and connection in today’s world… It’s an experience that has begun to feel exponentially more crucial, and more difficult, in recent weeks.

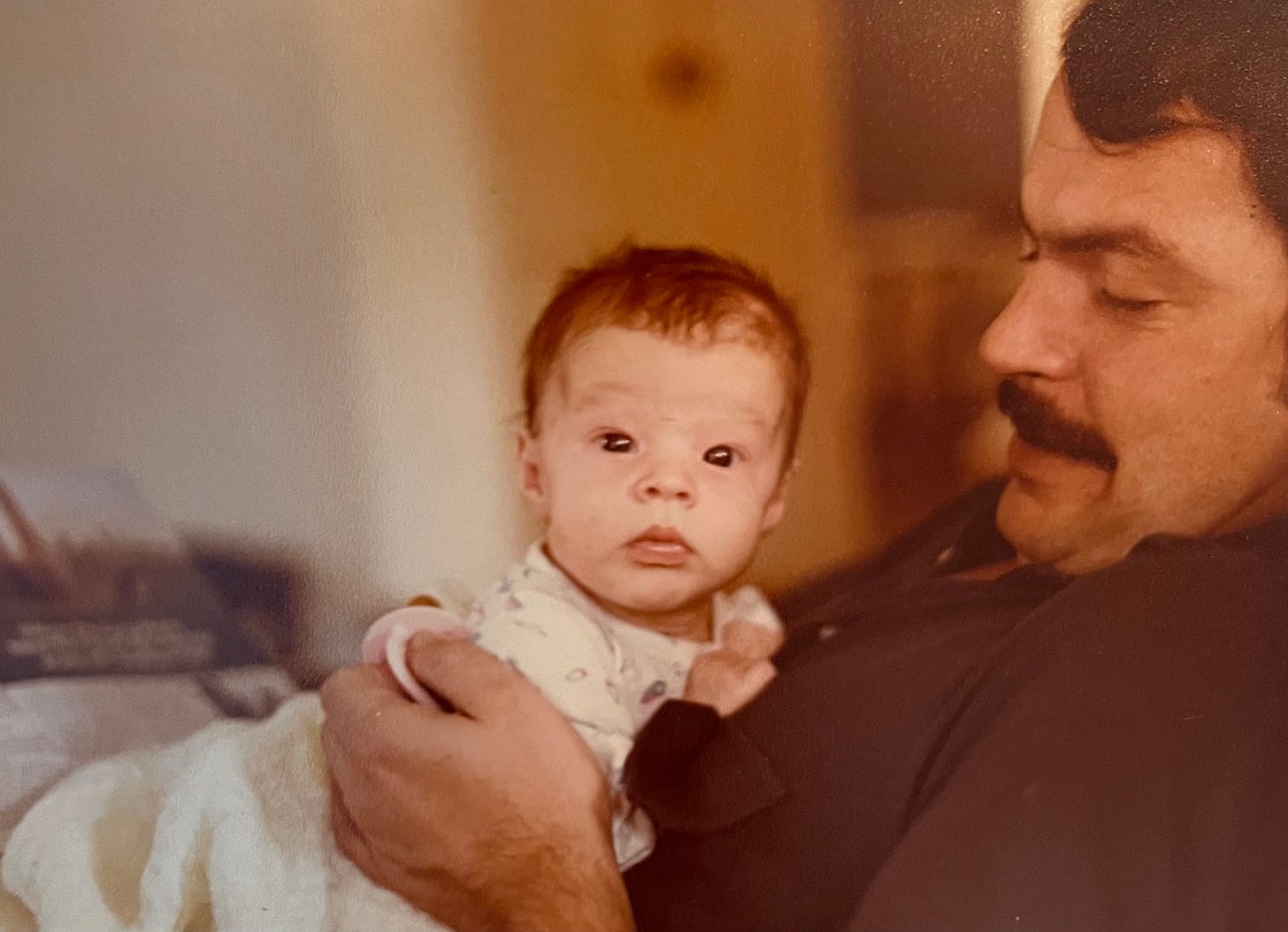

My Dad died two months ago. His death must have had something to do with my suddenly picking up Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death from one of the sky-high piles on my nightstand (yes that’s piles, plural) where it had been languishing for months, and finishing it.

My Dad and me, 1979.

The book follows a group of prominent late-19th Century thinkers and scientists who endeavored to prove the existence of “unexplainable” phenomena—things like clairvoyance, communication with the dead, telepathy. I’ve long had an interest in this tempestuous period of American history, the age of Darwin and electricity and numerous other discoveries and innovations that would forever alter our lives and our perceptions of the world. Other interests include: neurodivergence, illness and recovery, interconnectedness, the idea of “nature” as a human construct... If you’re familiar with “The Telepathy Tapes” podcast, you might see why I was intrigued on many levels when a dear friend (a friend, I must add, who is one of the all-around best humans I know, someone I’m constantly trying to learn from and hope to emulate in all things) first texted me a link to it.

If you’re not familiar with the show, here’s part of the description from its website: “In a world that often dismisses the extraordinary as mere fantasy, The Telepathy Tapes dares to explore the profound abilities of non-speakers with autism—individuals who have long been misunderstood and underestimated. These silent communicators possess gifts that defy conventional understanding, from telepathy to otherworldly perceptions, challenging the limits of what we believe to be real.”

Let me say right off the bat: I want to believe. I don’t NOT believe. I found The Telepathy Tapes initially fascinating, but increasingly problematic, and ultimately a bit infuriating, but not for the reasons you might think: it’s not because the show’s very premise—that nonspeaking autistic people can communicate telepathically—is crazy. (I try to be a skeptic, but I also know how much I don’t know. You know? Again: I want to believe). The way the show presents “evidence” is, I think, hugely problematic and unconvincing (and I’m sad to say that, because it’s fascinating and I believe that stuff like this does happen, and probably is happening in many cases like this, perhaps even the cases depicted on the show), but I’m not going to critique that aspect, here. My main issue has to do with something that feels more fundamental and more important, so much so that I’m compelled to share my thoughts about it at all, instead of letting it simply be an interesting entertainment. That issue has to do with stigma against, and stereotypes of, autistic people.* (I promise I will do my best to explain how this ties in to endangered species, and ongoing disagreement over whether and how to try to save them, if you’ll stay with me…). All to say: I have qualms about the effect that this podcast will have on perceptions of autistic people .

*Important note: It’s my understanding that people with disabilities, autism in this case, are the ones who should choose how they want to be identified—whether that’s as “a person with autism” or “an autistic person,” or not to disclose at all, and so on… It’s an entirely individual choice. Moving forward in this particular post, I will use “autistic” as a descriptor, because the more I learn, the more I want to embrace and accept how this type of neurodivergence affects the entire person and that person’s experience of the world… And also because there should be no stigma around autism! But I respect people who say they don’t want to be defined by their autism, and see it as just one aspect of themselves…

Oh—also! Neurodivergent “is a nonmedical term that describes people whose brains develop or work differently for some reason. This means the person has different strengths and struggles from people whose brains develop or work more typically. While some people who are neurodivergent have medical conditions, it also happens to people where a medical condition or diagnosis hasn’t been identified.”

“If you’ve met one autistic person, then you’ve met one autistic person,”—so goes a popular saying, meant to illustrate the huge spectrum of individual particularities, interests and challenges that each autistic person experiences. For the sake of my own neurodivergent child’s privacy, I will refrain from including specifics about him, his diagnoses or challenges or gifts—it’s his story, as a wonderfully supportive friend once reminded me, aside from saying with his blessing that he is diagnosed with autism and ADHD. Suffice it to say that my child is very “low support needs,” what used to be called “high functioning,” a term very much out of favor now for very good reasons.**

**Another important note: As a good friend who is parent to a deaf, high-support-needs autistic child once told me, their kid “is the highest functioning person I know,” meaning that just getting through each day requires an incredible level of effort for that kid to “function,” doing what might seem basic things to a neurotypical person. Calling that child “low-functioning” is both misleading and inaccurate. On the flip side, the “high-functioning” label can, and often does, obscure and diminish the very, very real challenges that those with “lower support needs” face both in school and in the wider world. It’s hard to keep up with it all, honestly—the terminology changes and the discoveries being made—but important to try! The more you know, right?

There is a huge gulf between the challenges that many non-speaking, high-support-needs autistic people face and those of people who are on a different part of the spectrum—I want to acknowledge that. There is even debate about whether all the differences should be folded into one “spectrum” or not… So many debates...

But back to The Telepathy Tapes. A stereotype persists, among many horrible stereotypes, that autistic people are valuable only if or because they have “superpowers,” aka savant abilities (which only about 10 percent of autistics have), instead of being perfectly valuable and worthy human beings just as they are. (On a different but not entirely separate plane, this calls to mind debates over whether humans should help endangered species to survive, not because of how they serve us, or how they impact our environment, or how beautiful or valuable they are, but for the simple reason that they have a fundamental right to exist…)

Whether nonspeaking or having much lower support needs, autistic people can just be plain old regular humans, nothing more and nothing less. Neurodivergent folks don’t need to be angels or superhuman, as this podcast—to my great dismay—seems to clearly imply, however well-meaning the creator(s) may be. Heck, autistic people can even be jerks sometimes—maybe even evil! (Kidding…sort of… One would hope that jerk-like/evil behavior in any individual is potentially reversible, redeemable, if that individual sees the light… we are all multifaceted, all capable of goodness…).

An added complication with Telepathy Tapes is something the show addresses, sort of: the ongoing alleged controversy over assisted spelling, the manner in which nonspeaking individuals on the show are able to communicate their interior thoughts and experiences. I have no doubt that there are numerous nonspeaking kids that do find their voices this way, which is incredible—and it’s painful to see them being shut down by critics or skeptics who complain that aides or parents are in fact guiding them, and that their incredible breakthroughs in communication are not real… I worry that The Telepathy Tapes’ jumping right from the description of a non-speaker having a spelling breakthrough—in which, for example, a young adult whose parents were told that he/she would never speak, who was “not there” inside and maybe should be institutionalized, is now able to share their internal life via assisted communication, a truly incredible thing—to the less-graspable, less believable idea that all nonspeaking autistic people can communicate via telepathy, with dead people, are psychic, etc. It diminishes, in my opinion, the miracle of someone finding their voice after a lifetime in trapped silence. That would be podcast enough! No need for psychic powers.

(Honestly, just a podcast about non-speakers and what their lives are like, day in and day out, would go such a long way to reduce stigma and increase empathy, and would be fascinating in itself, even without a miraculous spelling breakthrough! But that would be, I realize, a completely different show... Perhaps one exists already…?)

My friend, the aforementioned parent of a deaf autistic child, in a brilliantly nuanced critique of the show (all of which I wish I could include here!), had a very interesting added point, that the parents and caretakers in the podcast talk about how “accepting these children not only as competent, but as having these spiritual or supernatural gifts, is key to advocating for their education and services, and that is so frustrating, if not infuriating… [it’s] actually harmful to the idea of advocating for their education, because what it does is it says, these kids, they don't need services per se. They have services to offer us…”

(The struggles that autistic people face in getting accommodations—hell, in just getting by in this world, day to day—are myriad, and their ability to receive crucial assistance, not to mention empathy and compassion and clear-sighted care, is in real freaking danger right now ).

Going further, my friend adds, “[These kids] have access to knowledge that we don't, but they have that knowledge through some combination of extraordinary sensory perception, or maybe through this field of like, a completely scrambled relationship between matter and information. It's so interesting, but what it's not is psychic. [With my own son], what I strive to understand is how I can learn from him—to look at other people, to look at the space I'm in, to look at nature, to look at my body, the the sensations in my body, and then to think about, what information does he have access to that I could have if I learned about perception from him? That what's interesting.”

The issues that bubbled up from thinking about and discussing The Telepathy Tapes reminded me of “the double-empathy problem,” referenced by the National Autistic Society of the UK among many other groups as a way to think about meeting neurodivergent people where they are, rather than expecting them to conform completely to a world that isn’t made for them: “Simply put, the theory of the double empathy problem suggests that when people with very different experiences of the world interact with one another, they will struggle to empathise with each other.” Once we try to begin to see how someone else experiences the world, rather than expecting them to fit into ours, we can open up the opportunity for insight and connection and mutual, reciprocal communication, to put it simply.

My friend’s description of how his son inspires him to reevaluate how he experiences the world reminds of one of the most incredible gifts that the experience of parenting an autistic kid has given me—an experience for which I am so profoundly grateful: I see the world now as filled with people like him, and also as a place that isn’t necessarily accommodating for them, a place in which they needlessly struggle, or are misunderstood at best, shunned or bullied at worst; a world in which we need to do better at trying to meet each other halfway, somehow. It’s increased my empathy, in the same way that any life experience does (after losing a parent, I now see how incredibly sad and hard it is, and wish I had been there more for friends who have been through this; so it goes, we live and learn, if we’re lucky).

This new awareness is more profound than just seeing things differently, which would be profound enough—it’s also by no means a halo I am now smugly wearing, to be very clear: I am constantly confronting internalized ableism, struggling and f—ing up: it’s like a paradigm shift, though, perhaps the way people feel after a transformative psychedelic trip, or a near-death experience. It’s still unfolding, of course, but I can say that it has altered how I think about and approach all humans, and even the point of life itself.

A valuable piece of advice that his old friend (and fellow parent of an autistic kid) shared with my husband, early on: “People are going to do their best, and they are still going to say and do the wrong things.” I have found this to be quite true—have since experienced so many moments in which truly kind and loving friends make comments about “weird” kids or over-concerned parents or other such things. But an added bonus of my paradigm shift is that it enables me not only to view neurodivergent people through a lens of curiosity and compassion, but also neurotypical friends who say and do things that are unintentionally hurtful or even offensive! More grace and compassion for everybody, is what I say! Lord knows I could use it, myself.

Where was I… I am feeling so fragmented these days, in case that’s not already evident. Heartsick. I was in tai chi class the other day (I love it, am going to write about it) and an elderly man’s skinny legs, visible in shorts, suddenly brought to mind a vivid, visceral image of how bony my dad’s legs were at the very end, and I had to leave class and go cry in my car. The first time I’d cried in a long time, which is surprising for me. Grief is strange like this—amorphous, ever-present under the surface. I’m learning to live with it, I guess.

Back to the Ghost Hunters book. William James, a prominent psychologist (and brother to famed author Henry James), who risked both his scholarly and professional reputation in order to pursue tests trying to prove the existence of phenomena like telepathy, wrote of a schism happening between religion and the then-newly-emerging field of science. Author Deborah Blum describes how through their '“determined orthodoxy, scientists had come to seem a mirror image of those clergymen who insisted on only one way of seeing the world,” and she quotes James as saying: “Science means, first of all, a certain dispassionate method. To suppose that it means a certain set of results that one should pin one’s faith upon and hug forever is sadly to mistake its genius and degrades the scientific body to the status of a cult.”

This brings me back to endangered wolves, and the schisms in our country, and the forced binary I’ve encountered in my half-decade of researching and reporting on them. A major realization for me, which might seem basic or obvious but nevertheless I keep running into as the major reason for so many challenges, has been the difficulty we humans have in accepting complexity and nuance, and that multiple truths can coexist. Hey: it’s hard! We aren’t programmed that way. And I heard somewhere (trying to remember where) that some people need more certainty, more structure and a feeling of “this is what I believe, this is what is” and others are naturally more accepting of mystery and uncertainty. I fall into the latter camp, but neither is better or worse—and anyway lumping all humans into two main camps is exactly the sort of thing I’m trying to illustrate as short-sighted, forget I said anything.

This was much longer, but I’m already so late in posting, so I’m going to wrap up. Both in this newsletter and in other writing projects I’m working on, digging into vast concepts like extinction and hope and survival, especially the ongoing struggle to save a little-known, critically endangered wolf from oblivion, I hope might help teach us something about how to move forward. How to begin to see and hear each other, and to try to accept the nuanced, multifaceted nature of so many conflicts. When I interviewed Regina Mossotti, then Director of the Endangered Wolf Center in Missouri, for a Vox series on the Biodiversity Crisis a couple of years ago, she acknowledged that “Conservation can be incredibly challenging”—referring not only to the need for rigorous science and for perseverance when initiatives fell short, but also to the challenges of dealing with humans, with all their complexity and contradictions.

“In an era when Darwinians faced off against the defenders of Genesis,” Blum writes in Ghost Hunters, “neither side allowing for a middle ground—both groups lost a measure of credibility and trust. The psychical research movement [in which James was involved] rose in response to such rigidity, built by those who believed that objective and intelligent investigation could provide answers to the troubling metaphysical questions of the time—and that those answers mattered.”

How could I read this and not think of the fierce, ongoing fighting about reintroduction and recovery of wolves, not only in my state but in the U.S.—and not only wolves but endangered species in general, whether or not money and resources should be spent to save them?

The idea laid out in the Book of Genesis, that man shall “have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth” certainly undergirds a worldview that affects how one might approach the existence of “apex predators” like wolves, and especially the reintroduction of species that have disappeared. In contrast: the view that living creatures all have equal worth, equal right to exist. That might be an incredible oversimplification. Over these past few years, I’ve been confronting my own biases while exploring the struggles that Americans have in communicating across political and ideological divides, and also trying to uncover how these divisions have contributed to the decimation of red wolves. As my own ideas about nature as a human construct evolve, I see firsthand what happens when living beings are reduced to symbols.

Red wolves are in increasing danger every day, their wild population steadily dwindling due to increasing vehicle strikes and ongoing poaching, as well as a thorny, ever-growing problem with coyotes. Some landowners in the region have long been pressuring both the state and federal government to end the recovery program and declare them extinct in the wild. What awesome power we have, to be able to declare a species unfit to exist outside captivity, largely because of how we have shaped this world. Coming from such varied backgrounds and worldviews, animals that we are at our cores, is it even possible for humans to achieve harmony with, or experience true empathy for, other forms of life? The struggle to live rightly in the world, as described by environmental historian William Cronon in his 1995 essay “The Problem with Wilderness,” forms the foundation of my investigation…

I’ve long been enthralled by Francine Madden of the Center for Conservation Peacebuilding—her extraordinary approach to human-wildlife conflicts, around the world, and the promise it holds for resolving the seemingly insurmountable divide in eastern NC. (This recent opinion piece illustrates wonderfully some of the work she is doing).

“It’s not easy to walk the line between worldviews,” Madden writes in the report People and Red Wolves: A Conflict Assessment and Recommendations, published last June (2024). At the time the report came out, I was re-reading Clarissa Pinkola Estes’s best-selling nineteen-nineties manifesto Women Who Run With Wolves, a book which feels both silly and profound—and why can’t it be both? As the incomparable Barry Lopez said in an interview not long before his death a few years ago, “Life without contradiction would collapse.”

False binaries are confronting me everywhere, these days: “Dependence and independence, wildness and refinement, purity and filth. To collapse the categories is to acknowledge our fundamental interdependence with all other beings,” writes Lisa Wells in Believers: Navigating a Life at the End of the World. The effect of the collapsing of categories that she describes is itself a paradox, as it “both comforts and terrifies.”

Sunset in the Alligator River Refuge

I’m going to stop here! It’s hard to focus these days, with all that’s happening in the world. I hope this has provided a little food for thought, at least. I’d love to hear from you.

Friday Solace (late):

Here are a few things that have brought me joy or wonder or at least diversion this week:

This video of a superpod of dolphins off the California coast:

Going to a (free!) black history month event with my daughter at Empower Dance in Durham which highlighted black choreographers and different styles of dance. I learned so much and the dancers at Empower consistently take my breath away. Sharing this photo because it doesn’t really share any of their faces

Crochet lessons!

Italo disco — which a friend described as “both relaxing and energizing” which shouldn’t be possible but is, in fact, true:

Welp there's a paragraph that repeats in here--I wanted to post something at last, after getting held up all week... Once it's posted it's out there and (I don't think) I can change without deleting. Forgive the very light editing found here, please